Upstream Barriers, Downstream Crisis: Denial of Justice under BC’s Mental Health Act

These are summaries from the publication. We encourage you to read the full publication for more information.

How and why we did this work

“I already knew that there were things that I had the right to do, but that I wasn’t supposed to do. And if I did them, I would be punished.”

-

A primary focus of Health Justice’s work is advocating for reform to BC’s Mental Health Act. Health Justice uses a participatory engagement governance model that centres those most impacted by our work. To develop this publication, we have been listening and learning since 2020 through in-depth interviews, focus groups, and other forms of engagement with people with lived and living experiences trying to access justice as an involuntary patient under the Mental Health Act. All of the thoughts, ideas, and analysis in this publication have been built upon expertise and analysis that has been shared with us by the Lived Experience Experts group and other experts with direct lived and living experience, the Indigenous Leadership Group, family members/personal supporters, health care providers, and other organizations.

-

Whenever state power is exercised to detain and infringe fundamental rights, those impacted must have a way to access justice. The Charter and international human rights instruments require effective access-to-justice safeguards for involuntary patients under the Mental Health Act. Access to justice provides transparency to see how powers are being exercised, safeguards to ensure detaining authorities exercise their powers appropriately, accountability when powers are misused, and meaningful remedies for someone whose rights are violated.

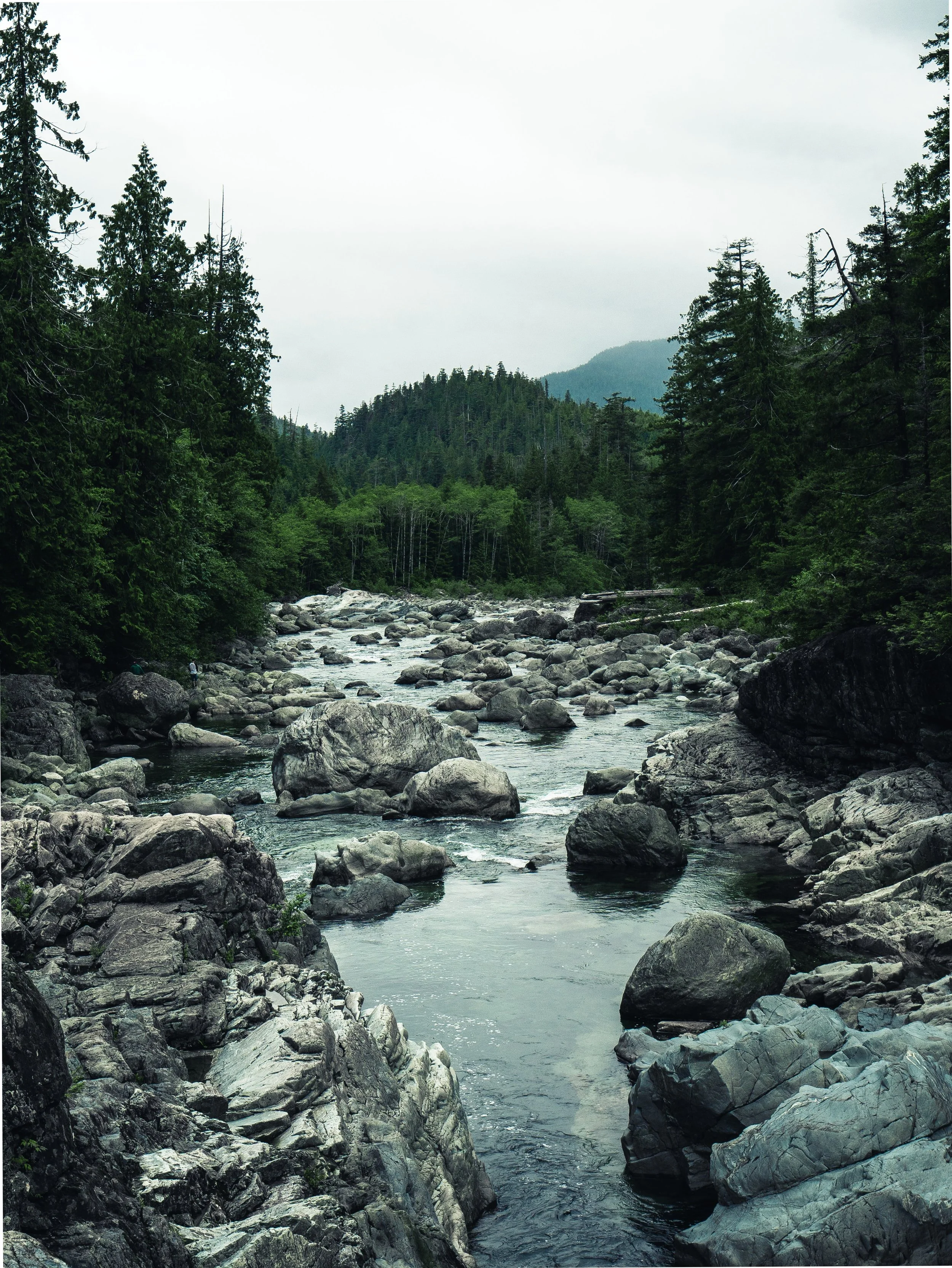

Access to justice can be understood as a stream or river that a person is trying to travel along. Barriers upstream create ramifications for navigation downstream. Systemic reports, data, and case law show that access to justice rates have become worse in recent years for people impacted by the Mental Health Act. First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people face unique access-to-justice barriers when detained and experiencing involuntary treatment under BC’s Mental Health Act. BC must address access-to-justice barriers because providing involuntary patients with as much choice, voice, and participation as possible can reduce the harms of detention and coercion and promote better health outcomes.

Access to rights information, legal advice, and legal representation

“Any one patient is not going to know the protocol of doing something like this. Having a lawyer is extremely valuable.”

-

Learning that you have rights when you are detained under the Mental Health Act is a necessary first step before any further justice mechanisms can be accessed. Overwhelming evidence shows that detaining facilities and mental health teams are failing to comply with legal obligations to inform involuntary patients of their rights. A new independent rights advice service is being established in BC, but it is too soon to evaluate how accessible and effective the service will be.

-

When you are detained in Canada, the Charter requires the detaining authority to inform you of your right to a lawyer without delay. However, there is no government-funded program or service that has been established for the purposes of providing legal advice to people detained under the Mental Health Act in BC. Legal Aid BC may provide access to legal advice for people who qualify, but it does not have any publicly available information that it will consider requests for legal advice for Mental Health Act detention issues and it does not track the number of people who have made these requests.

-

Involuntary patients are entitled to legal representation at review panel hearings before the Mental Health Review Board and the court. There is an established, legal aid–funded service available for involuntary patients who meet criteria to access free legal representation for review panel hearings. Despite this, barriers mean a significant portion of involuntary patients are still going to review panels without legal representation.

The majority of legal representation at review panels in BC is provided by legal aid lawyers. Legal aid lawyers are paid substantially lower rates for representation at review panel hearings than other legal aid work. This disparity in compensation negatively impacts the experience of involuntary patients at review panels and the quality of legal work lawyers are able to do.

Involuntary patients have the right to pursue a number of different court applications. Legal Aid BC may provide access to legal representation for court applications for people who qualify, but it does not have any publicly available information that it will consider these requests. Nobody has received legal aid funding for legal representation in a Mental Health Act-related court application in the last 10 years.

Access to review panels and courts

“My understanding is that court looks at whether the paperwork is in order. I don’t know if the court does anything else.”

-

The Mental Health Review Board is an independent tribunal that holds review panel hearings. Access to the Mental Health Review Board is rare for involuntary patients. While detention rates have been steadily increasing, access to review panels has not kept pace with those increases.

The publication considers four aspects of review panels that impact access to justice for involuntary patients:

The Mental Health Act puts the onus on involuntary patients to request a review panel hearing. This means that you can be detained for the rest of your life without any independent review from an adjudicator outside the detaining facility. In contrast, legislation in other places in Canada create automatic hearings at certain intervals to ensure built-in access-to-justice safeguards.

The Mental Health Review Board has jurisdiction (authority) to perform one function: review detention to consider whether the legal criteria continue to be met. This limited scope of jurisdiction leaves many involuntary patients with no where to turn for many questions, concerns, or issues they experience during detention or involuntary treatment. In contrast, legislation in other places in Canada provides the tribunal with a broader scope of jurisdiction to consider other questions, concerns, or issues that involuntary patients face.

The Mental Health Review Board’s budget must be sufficient to ensure accessible and fair hearings, but it appears to be lower than other comparable tribunals. The Mental Health Review Board’s practice of funding the party presenting the case for detention and not the party presenting the case for discharge is unbalanced and it creates concerns for partiality to or lack of independence from detaining facilities.

Review panels involve complex legal principles, conflicting fact and opinion evidence that must be considered and weighed, and high potential for distress, harm, and trauma. Involuntary patient experiences at review panels can be greatly impacted by tribunal member qualifications, diversity, and training; cultural safety in review panel hearing processes; safeguards against conflict of interest, bias, or apprehension of bias; and review panel procedures.

-

Involuntary patients have the right to pursue a number of different court applications, including habeas corpus applications, s. 33 applications, and judicial reviews of review panel decisions. Courts have a fundamental role in Canadian society to safeguard constitutional rights, interpret legislation, supervise tribunals, and provide independent oversight to detaining authorities. Even when a tribunal is established to review detention, courts play a unique and important role that cannot be fulfilled by tribunal proceedings alone.

The barriers to court are so significant that access to courts is a theory, rather than reality for involuntary patients. There have only been a handful of published decisions brought by an involuntary patient in the last 10 years out of the hundreds of thousands of people detained and experiencing involuntary treatment. Without meaningful access to the courts, safeguards that were included in the law to provide a check and balance to the Mental Health Act’s powers are not functioning as intended.

The barriers that are blocking access to justice are cumulative and, when combined, make routes unnavigable for people impacted by the Mental Health Act in BC. Upstream barriers create devastating downstream impacts. It is clear the Mental Health Act needs holistic review and reform. The BC government, actors in the health and legal systems, and members of many other communities have significant power to transform BC to a place that welcomes justice as necessary for well-being in our mental health and substance use health care system.

There will be a plain text version of this publication available in the future.

Community Reflections

This publication was funded by the Law Foundation of BC.

Previous work in this area

Advocating for Rights Advice

For decades BC was one of the few provinces in Canada that did not have a service built into its mental health legislation to provide people with independent information and assistance to learn about their rights when detained under the Mental Health Act. In 2021 Health Justice and many community partners joined together to advocate for the BC government to address this gap. In 2022 the BC government passed changes to the Mental Health Act to allow an independent rights advice service to be established. The Independent Rights Advice Service is currently being gradually implemented across BC.

Alt text for image above: Graphic of a community vision for independent legal advice services for people detained and experiencing involuntary treatment under the Mental Health Act.

-

Independent legal advice services (ILAS) are person-centered advocacy models designed to promote self-determination and personal recovery for people experiencing mental health detention and involuntary mental health and substance use health care. Some key functions include:

Providing legal information and advice to involuntary patients about the laws they are subject to;

Providing legal information and advice to involuntary patients about their legal rights; and

Providing assistance, advice, and support to involuntary patients to exercise their rights and participate in decisions impacting them.

-

This community vision was developed in partnership with the Lived Experience Experts Group and the Indigenous Leadership Group.

INDEPENDENT: ILAS must be independent from government, health authorities, and designated facilities to ensure it is a confidential and trusted resource for patients.

AUTOMATIC: Access to ILAS must be automatic, with a choice to opt-out. Removing the onus to request the service eliminates barriers.

WRITTEN IN LAW: A legislative mandate for the service will establish necessary roles, access to information, and protection from service cuts.

CO-DESIGNED: People with lived and living experience of involuntary treatment under the Mental Health Act are diverse experts on what makes ILAS effective. They must be meaningfully involved in the design and delivery of the service alongside Indigenous leaders in compliance with the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, cultural safety experts, human rights experts, and mental health law experts.

CENTRALIZED: ILAS must be overseen by a centralized agency to ensure consistency, quality, and coordination.

TRAINING FOR ILAS PROVIDERS: ILAS service providers must have training that includes lived experience expertise, mental health law, trauma-informed expertise, youth-specific service delivery, cultural safety, and anti-racism.

TRAINING FOR FACILITIES: Detaining facilities must be supported by independent education to increase understanding of ILAS and ensure effective cooperation between ILAS and facility staff.

USER-CENTRED: ILAS must be delivered by staff that reflect the diversity of people who access the service, including peers, Indigenous-led services for Indigenous patients, and other targeted ways to ensure accessibility.

IN-PERSON: ILAS must be provided in-person where possible to ensure accessibility, understanding, and the full therapeutic and legal benefits of the service.

EVALUATED: ILAS must be regularly evaluated via an independent process that includes lived experience expertise.

-

BC is one of the few Canadian provinces that does not have some form of independent legal advice and advocacy services for involuntary patients detained under civil mental health legislation.[1]

Multiple investigations in BC have found that involuntary patients have not been notified of their rights by facility staff at all, or in a way that involuntary patients understand.[2] For example, the Ombudsperson found that 51% of files were missing the document that shows an involuntary patient was notified of their rights and the rights notification was not completed properly or promptly in many other files.[3]

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees everyone the right to access a lawyer when they are detained. When detaining facility staff do notify involuntary patients that they have the right to access lawyer, there is no established service for them to contact for legal advice and advocacy.

The absence of independent legal advice and advocacy services for mental health detainees in BC has created an access to justice crisis in BC:The rates of Mental Health Act detentions have been increasing dramatically, with over 28,000 detentions in the most recently reported year. The detention rate has more than doubled in the last 14 years.[4]

Despite this increase, the number of involuntary patients accessing their right to independent review of detention at the Mental Health Review Board has not only failed to keep pace with the increases in the detained population, but actually decreased in recent years, down to only 811 hearings in its most recently reported year.[5] That means only approximately 3% of detentions are independently reviewed.

1 in 3 involuntary patients is conducting a legal proceeding to challenge their detention at the Mental Health Review Board without legal representation.[6]

-

Research documents that people who have been detained or involuntarily treated under mental health legislation report that the experience can be frightening, confusing, disempowering, and made them feel helpless.[7] There is a risk that regardless of the intention, the coercion inherent in involuntary treatment can reduce potential benefits of treatment, create counter-therapeutic harms or trauma for patients, and lead to alienation from health and social services in the future.

Evaluations of independent legal advice services have found many benefits, including:Increasing service users’ well-being, confidence, and recovery goals;

Assisting health care systems in addressing anti-racism and equitable service provision (for instance, the services can be particularly useful to racialized and Indigenous people who research shows may be subject to higher levels of coercion in the mental health system);

Enhancing and empowering patient participation in decision-making around care and treatment;

Reducing isolation and improving communication and connection with family, friends, and community based mental health services, which could prevent future mental health crises;

Supporting health care systems to make improvements in culture and practices, fostering greater accountability, reflection, and transparency among treatment teams;

Facilitating more constructive relationships and defusing conflict between service users and detaining facility staff;

Mitigating health care delivery risks for detaining facility staff and increasing the rate of successful complaint resolution; and

Improving quality of care and life for service users and acting as a safeguard against poor or inconsistent practices.[8]

-

[1] Ombudsperson’s Special Report No. 42, Committed to Change: Protecting the Rights of Involuntary Patients under the Mental Health Act (March 2019), p. 84.

[2] See for example, BC Ministry of Health and Ministry Responsible for Seniors, “Impact Assessment of the Amendments to the Mental Health Act of British Columbia”, by Ayne Meiklem (March 2000), p. 20; R.A. Malatest & Associates Ltd, Patient Experiences with Short-Stay Mental Health and Substance Use Services in British Columbia (November 2011), p. 27.

[3] Ombudsperson’s Special Report No. 42, Committed to Change: Protecting the Rights of Involuntary Patients under the Mental Health Act (March 2019), p. 34.

[4] Moira Wyton, Forced Mental Health Treatment Spikes in BC, The Tyee (November 23, 2021).

[5] Mental Health Review Board 2019/2020 Annual Report (September 9, 2020), p. 14.

[6] Mental Health Review Board 2019/2020 Annual Report (September 9, 2020), p. 23.

[7] The Right to Be Heard, p. 3-4, 58, 186; Honouring the Past, Shaping the Future: 25 Years of Progress in Mental Health Advocacy and Rights Protection, Psychiatric Patient Advocate Office 25th Anniversary Report, (2008), p. 109.

[8] The Right to Be Heard: Review of the Quality of Independent Mental Health Advocate (IMHA) Services in England, University of Central Lancashire (June 2012), p. 4, 9, 20-21, 25-27, 83-84, 192-202; Ombudsperson’s Special Report No. 42, Committed to Change: Protecting the Rights of Involuntary Patients under the Mental Health Act, (March 2019), p. 2, 9, 13, 15, 38-39, 169-170; Honouring the Past, Shaping the Future: 25 Years of Progress in Mental Health Advocacy and Rights Protection, Psychiatric Patient Advocate Office 25th Anniversary Report, (2008), p. 2-3, 32-34, 39, 107.