Seclusion and Restraints in BC: What we know and what we don’t

Content note: This blog post discusses the use of seclusion and restraint and the impact it has on people. Please see this page for resources.

Terminology

-

Seclusion is the practice of isolating a person by confining them to a specific space, often by locking them in a specific room (sometimes also called a Secure Room in BC). In practical terms, like room design and the experience of extreme isolation and deprivation, seclusion amounts to solitary confinement, although the institutional and power context in the health system may be different than other uses of solitary confinement, including in the prison system.

-

Restraint is the use of other methods of restricting a person’s freedom of movement or mobility. In the psychiatric context, this includes:

Mechanical restraint: when a device is used to immobilize a person or restrict free movement. For example, this could include belts or straps that restrain a person to their bed.

Physical or manual restraint: when a person or people apply manual force with their hands or bodies (without the use of a device) to restrict a person’s free movement or activity. For example, this could include physical holds by security guards using the force and weight of their bodies to restrict a person.

Chemical restraint: when medication is used with the intent to sedate a person so their movement/behavior is restricted instead of with the intent of administering medication for a therapeutic benefit.

BC’s Mental Health Act states that every involuntary patient is “during detention, subject to the direction and discipline” of facility staff. This disciplinary power has been part of the Mental Health Act since the original law was passed in 1964. It allows patients to be solitarily confined in seclusion rooms, mechanically restrained with straps that tie them to their beds, or held with physical force by other people during their time in the hospital. While psychiatric institutions like Riverview have closed and some of the language and practices around psychiatric detention and treatment have changed since 1964, the authority to punish people in the name of treatment has persisted.

“There's a dangerous disconnect that occurs when individuals are labeled as 'mentally ill.' It creates an 'us vs. them' mentality, where maltreatment that would be considered unacceptable in any other context, becomes normalized... This justification is often rooted in the misconception that patients with mental illness are inherently dangerous or violent. In reality, restraint and seclusion are frequently used to enforce compliance, even in cases where there is no threat of harm.”

— Lived Experience Expert

As we have written about previously (Guiding Principles, Fast Facts), direction and discipline are significant legal powers authorized by the Mental Health Act that grossly limit an involuntary patient’s agency, autonomy, and ability to move freely. Facility staff control:

when a person experiencing involuntary detention is allowed to leave a facility,

how long they are allowed to leave the facility for, and

whether and when they can connect with loved ones.

These necessities are often treated as privileges that can be given and taken away, all under the authority of direction and discipline. Regarding seclusion and restraints, facility staff also decide:

the reason for their use,

how they should be used,

how often they are used,

how long they are used for,

what method should be used and when, and

what information is documented about their use.

BC’s lack of accountability and oversight for the use of seclusion and restraint and the resulting harm

The use of seclusion and restraint is a serious threat to an involuntary patient’s right to be free from harm and to decide what happens to their body. Any use of seclusion or restraint impacts a person’s right to life, liberty, and security of their person under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Given what is at stake, you might assume that such a severe and invasive power under the Mental Health Act would be balanced by strict, exhaustive mechanisms to minimize its use. Instead, BC’s Mental Health Act does not place any limits on when, how, or why someone can be subject to seclusion or restraints. There is no requirement that it be a last resort or only used to address serious safety risk. It also does not include a single safeguard for this unlimited power, including for children and youth, who are equally subject to direction and discipline under the Act.

“They didn’t need to seclude me like they did. They could have talked to me. Because, I mean, it wasn’t necessary. I wasn’t actually, like, threatening violence to anyone. I wasn’t being violent. I wasn’t being violent to myself.”

— Lived Experience Expert

There is no independent oversight of the use of seclusion and restraint, no way to review how and when they are used, and no accessible means to challenge their use. There are no safe, accessible ways in which an involuntary patient could hold a facility, health authority, or individual health care provider accountable for any disciplinary decisions. Lived Experience Experts have emphasized that the effects of seclusion and restraint do not go away upon discharge, and that they are left having to recover from the same system that was supposed to help them heal. BC’s mental health system offers no support for healing from the harm that it causes.

“Because you have no control, you have no power in that. You’re locked… you’re a prisoner… you’re held captive. And I just get scared—what if someone on a power trip wants to do something bad?”

— Lived Experience Expert

Even without legislated limits or safeguards, the Ministry of Health could develop mechanisms to ensure any use of seclusion or restraint under the Mental Health Act is monitored, evaluated, and reviewable. They have yet to do so. Decisions on the use of restraints have been left to regional health authorities and individual facilities, creating a patchwork of policies and standards out of reach of public scrutiny. The most recent provincial guidance on the use of seclusion was published in 2014. Even that policy admits that seclusion is harmful and that there is no evidence that its use contributes to healing or recovery. However, the standards established in that policy fail to empower patients or protect them from harm. The standards do not place any time limits on the duration of seclusion or the frequency of its use. They do not create any specific standards or safeguards for children and youth. They state that seclusion should only be relied on as a short-term, emergency measure of last resort, but fail to create any way to guarantee that in practice.

What does lived experience tell us about the use of seclusion and restraints in BC?

The use of seclusion and restraint is normalized in BC’s mental health system. Lived Experience Experts have shared that seclusion is often used in situations well outside those that could be considered a short-term emergency measure. They report it being used regularly as a threat to compel compliance or a punishment for non-compliant behaviour.

“When I was restrained and secluded, I was afraid. I was told to take off my clothes and put on scrubs. My admission had been so rapid that I couldn’t quite believe they were keeping me and I said ‘can I just have a minute to process that all this is happening’ and the nurse said ‘that’s it, she needs to be restrained, she’s resisting’. They simply didn’t want to wait so they tied me to a bed and stripped me. It was as if I was no longer seen as a person deserving of basic respect and dignity. They left me tied to a bed.”

— Lived Experience Expert

They also shared with us the terror and trauma associated with experiencing seclusion and restraint. These included experiences like:

the use of physical force on their bodies by multiple security guards,

forced removal of clothing,

involuntary sedation without being told what is happening, and

being left confined to a room or a bed, unable to move freely or at all, with no idea of when it would end.

“For me, the seclusion rooms are traumatizing. You are trapped, you are captured. You are held in a cell. You feel like you’re held in a dungeon or some guy’s basement.”

— Lived Experience Expert

As demonstrated in the quotes above, there is great harm in the unrestricted use of seclusion and restraint in BC. The true impact on people, and their trust and relationship with the health care system, can be irreparable and are often not acknowledged or addressed in the mental health system.

What does data tell us about how seclusion and restraint are used in BC?

Data on how the Mental Health Act is applied in BC is not made public, including how seclusion and restraint are used. There are also no publicly available reports or data regarding health authority or facility compliance with the provincial standards or seclusion room policy guidelines. Without this, we have no way of knowing how seclusion and restraint are used and whether the minimal guidance in place is even being followed.

Health Justice obtained limited data on seclusion and restraint use from the Ministry of Health through a Freedom of Information (FOI) request submitted in 2023. We learned that data on seclusion and restraint was not reliably collected prior to 2020/21, despite the provincial standards requiring data reporting being in place since 2014. We also learned that the data collected is incredibly limited and fails to provide a thorough picture of how seclusion and restraint are being used in British Columbia.

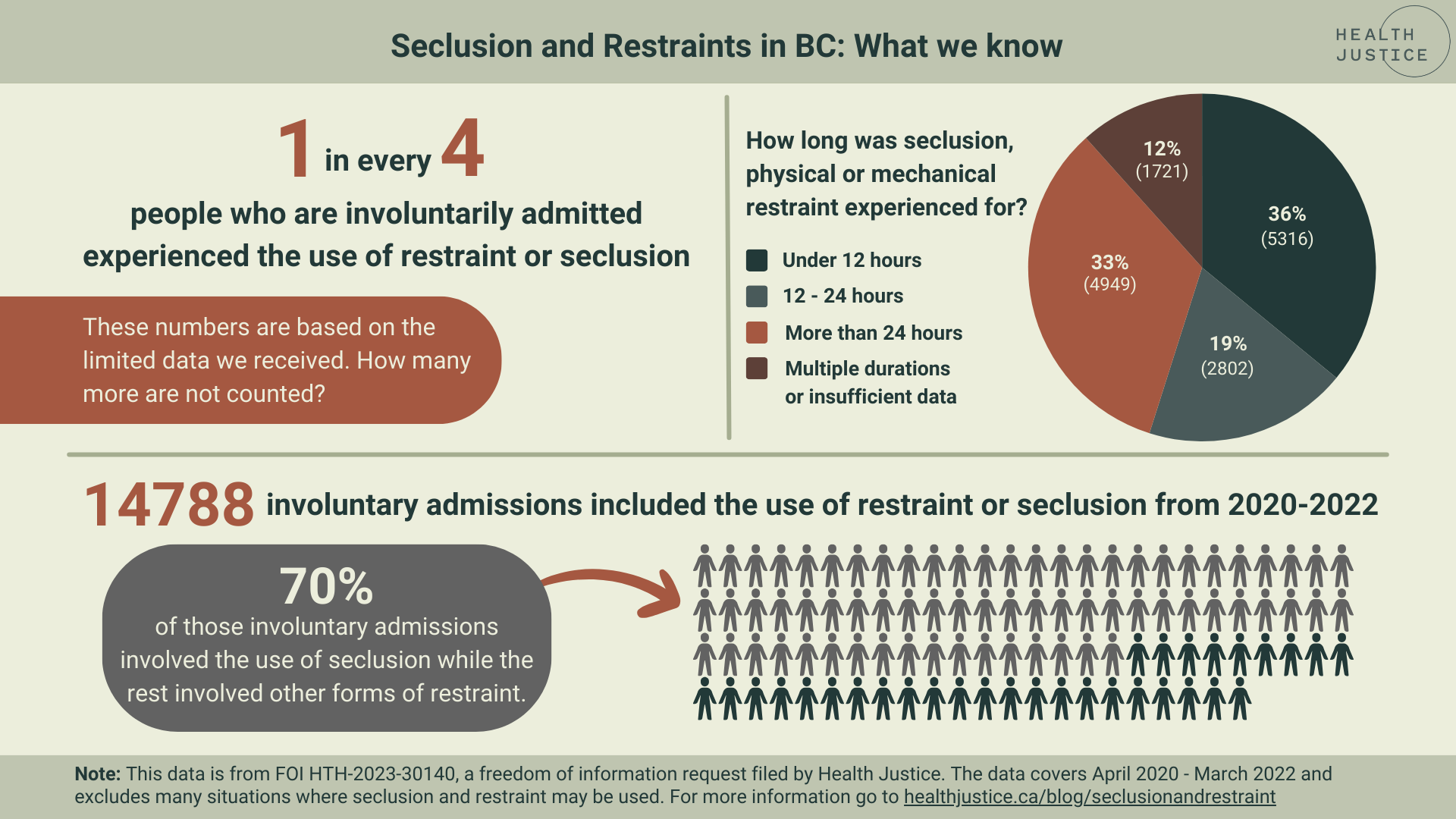

Based on the limited data shared by the Ministry of Health in response to our FOI request, we know that between 2020/21-2021/22, roughly one in four (14,788) of all involuntary admissions included seclusion, physical, or mechanical restraint. The most commonly used method of restraint was seclusion rooms, which accounted for approximately 70% of all admissions that involved the use of some form of restraint. BC does not collect data on how long a person experiences seclusion and restraint beyond 24 continuous hours, but we do know that:

36% (5,316) involved continuous use for 12 hours or less

19% (2,802) involved continuous use for 12-24 hours

33% (4,949) involved continuous use for more than 24 hours

12% (1,721) were assigned to categories “multiple durations” or “insufficient information”

Click the image below to open it in a new tab. Click here for a pdf version.

Description for the image above: This image depicts varying types of data that was found when reviewing the use of seclusion and restraints during involuntary treatment BC from April 2020 - March 2022. It shows that 1 in every 4 people who are involuntarily admitted experienced the use of restraint or seclusion. It also shows in a pie graph how long seclusion, physical or mechanical restraint was experienced for. There is a graphic of a crowd of people in two different colours to show that of the 14788 involuntary admissions that included restraint or seclusion, 70% experienced seclusion while the rest involved other forms of restraint.

What experiences are we not counting in BC’s data collection?

While these numbers are significant, they are incomplete and undercounted. In many ways, the data told us more through what was left out:

Data on seclusion and restraint has only been reliably tracked since 2020/21, so it is impossible to evaluate how seclusion and restraint have been used over time.

The data only tracked the use of seclusion and restraint for the first three days of a patient’s hospitalization, and even then, it only counts admissions where seclusion or restraint were used and not the number of actual incidents of seclusion or restraint. This means that if a person was secluded or restrained outside of the first three days of admission, it would not be counted.

The data does not include the use of chemical restraints, like sedatives. It also doesn’t include restraints used while in police custody, like handcuffs, when police apprehend someone under the Mental Health Act.

The data does not account for every facility where someone might be detained under the Mental Health Act and does not include use of seclusion or restraint where the person is not ultimately admitted as an involuntary patient. For example, if someone is held in an emergency department and then released.

There is also no demographic information included in the data we received, and we understand it is not available. This means that we have no information about how seclusion and restraint are used based on age, gender, race, or other factors. This is especially concerning given what we already know about the use of seclusion and restraint like the fact that racialized people are often overrepresented in those who experience seclusion and restraint (Time for a Paradigm Shift, Disparities in Care, Seclusion Report). We also know about the reality of gender-based violence in BC’s mental health system and the ways that harm in this colonial system disproportionately impacts Indigenous people. We know that legislation and policy have provided zero safeguards for children and youth exposed to direction and discipline under the Mental Health Act, including the use of seclusion and restraint. In the 2021 report Detained, the Representative for Children and Youth noted concerns about the reliability of seclusion data from the Ministry of Health, but shared that according to data from 2018/19, some young people were placed in seclusion rooms multiple times and 38% of children and youth held in seclusion rooms were 15-years-old and younger.

From this, it is clear that BC’s tracking of the use of seclusion and restraint fails to monitor the whole picture and is missing crucial aspects of information for meaningful accountability and oversight.

Ireland as a case study: What can BC learn from what others are already doing?

There are other mental health systems in the world that incorporate oversight and accountability mechanisms currently non-existent in BC. Ireland’s mental health system is regulated by the Mental Health Commission, which inspects and reports independently on the quality and safety of mental health services in Ireland. The Mental Health Commission in Ireland establishes rules and codes of practice for the use of seclusion, physical, and mechanical restraints. They also report annually on:

how and where seclusion and restraint are being used,

which staff used seclusion and restraint,

who is affected by their use,

and whether such use is compliant with the rules and codes of practice.

Demographic data is also tracked and published, so we can see how gender, age, race, and status (for example, voluntary or involuntary) under Ireland’s mental health law influence the use of seclusion and restraint. The Mental Health Commission also tracks the primary reason for use of seclusion and restraint, duration of use, and other factors.

Ireland’s mental health service model builds on data collection and transparency with accountability measures that BC could learn from.

The use of seclusion and mechanical restraint is addressed in Ireland’s mental health law, which also authorizes the Mental Health Commission to make legally-binding rules on the use of seclusion and mechanical restraint. Failure to follow these rules is considered an offence under Ireland’s mental health law.

Each facility providing in-patient mental health services must register as an Approved Centre with the Mental Health Commission and must be inspected at least once per year.

As part of the annual inspections, the Inspector rates the compliance of each Approved Centre against the rules and codes of practice regarding seclusion and restraints.

Each Approved Centre is either found compliant or not compliant for each rule and if non-compliance is found, a detailed explanation is provided.

Inspection reports are publicly available for each Approved Centre.

If found non-compliant, Approved Centres can have conditions placed on their registration to address their non-compliance and in some cases can be removed from the register altogether.

This brief overview of Ireland’s mental health system shows how legislation, monitoring, reporting, and data collection can work to create a measure of accountability within a mental health system.

A seismic shift is needed in BC’s mental health system

We know that acknowledging harm is the first step towards being accountable for it and ensuring harm does not continue. Part of acknowledging systemic harm is making it visible. Data collection and transparency is one of the most basic ways to bring the use of seclusion and restraints into the light. It is a necessary first step towards evaluating a system with few limitations and safeguards. It is critical exposure of a law that significantly overrides a person’s Charter and human rights. Accessible data allows the public to see how the law operates systemically by showing who is disproportionately impacted, where the use is concentrated, how use is changing over time. Data collection is also the bare minimum in a system that is fundamentally broken.

Far beyond the closure of Riverview, direction and discipline continue to permit total control over people experiencing involuntary detention. We now know that at a minimum, about one quarter of all involuntary detentions involve the use of seclusion or restraint within the first three days of admission alone. With close to 30,000 Mental Health Act detentions in BC each year, the continued unregulated and unlimited use of this physical and structural violence is unacceptable. A culture without accountability is a shield for a system where treatment can be traumatic. BC’s Mental Health Act has permitted direction and discipline to take place out of sight and out of reach of any kind of recourse for over sixty years. It’s time for this extraordinarily invasive and harmful exercise of power to meet rigorous oversight and accountability.